Is The Cultural Zeitgeist As Abnormal As It Seems?

Dante’s Inferno and Lasch’s The Culture of Narcissism are two complementary lenses that provide a combination of metaphysical and psychological tools to understand the flaws of American society.

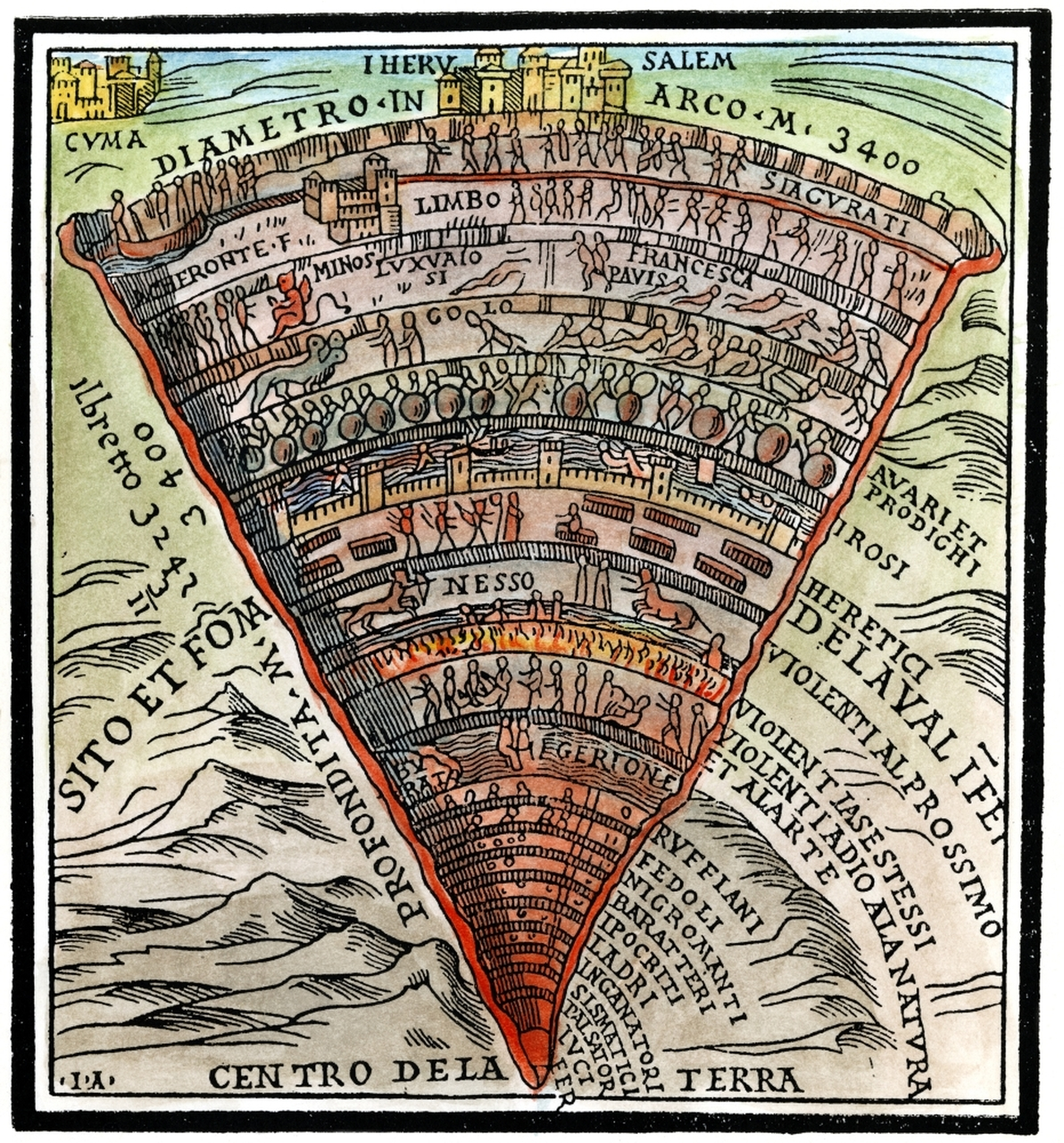

For those unfamiliar with it, The Divine Comedy is Dante Alighieri’s most famous work that details the medieval Italian poet’s dream of traversing Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Dante devotes a separate poem to each of these three domains—Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. Inferno is a meditation on the nature of human sin—specifically what internal attitudes cause a person to sin, what constitutes sin, and what are the consequences of sin. In the Inferno, Dante appears as a character who follows Virgil through the nine circles of Hell, witnessing the torment within each circle, culminating in their meeting Lucifer in the final circle and then exiting Hell. Sin takes on two forms, a suffering that the individual committing the action endures and a corresponding suffering that society endures due to the individual’s corruption. Through this duality, Dante comments on corrupt individuals within medieval Florence as well as the degradation they inflict on Italian societies.

The historian and social critic Christopher Lasch released his book The Culture of Narcissism in 1979 and similarly traces the individual pathology of narcissism from psychoanalytic roots to narcissism’s cultural and institutional manifestation. The narcissism described within his book differs from what psychiatrists detail in the DSM, providing a definition that encompasses a wider variety of behaviors that ultimately share a root cause. Throughout the book, Lasch repeats themes of how an individual’s pathologies, when prevalent in enough of the population, lead to emergent corresponding problems within a society’s culture and institutions. In a sense, Lasch’s concept of cultural zeitgeist acts as a living organism collectively mirroring the development and state of the individual psyche.

So what does Dante have to do with Christopher Lasch? In Divine Comedy, the character Dante makes statements about universal facets of human nature. The three domains through which he journeys serve as a vessel for understanding human existence and spiritual transcendence. Although the poet necessarily presents themes derived from Christian theology, we can easily decouple them from broader philosophical statements. Thus, we may use what Dante considers to be fundamental to human nature and The Culture of Narcissism and the state of modern Western society and, with care, propose solutions to the identified cultural flaws.

II.

Lasch defines the narcissist as one who crafts an inauthentic identity to be put on display to the outside world and treats reality as a mechanism of reinforcing this identity. They transform the external world into a repository of symbols by which they may construct their internal life; there is a compulsion for image maintenance that drives the narcissist, with fear of the internal void lingering in the case the facade is unobserved. Dante would call this fraud and send the narcissist to the eighth circle of Hell. It is fraud in that the individual attempts to sell the simulacrum of their real self as though it were the authentic self, and with the fraud comes all of the associated cultural and individual pathologies. Lasch captures this notion of fraud as he writes of the narcissist’s inability to have genuine and satisfying relationships:

...his fear of emotional dependence, together with his manipulative, exploitative approach to personal relations, makes relations bland, superficial, and deeply unsatisfying.

Authenticity becomes defaced, employed as nothing more than a strategic tool. The narcissist engages in hollow and vacuous self-examination, done in a detached manner to distance themself from the responsibility of self improvement. We see this attitude in our culture through the pervasive nihilism that lurks in public performances of authenticity and realization, as well as in private, as narcissists attempt to display carefully crafted narratives of growth in line with what the zeitgeist deems accessible. It is simultaneously ironic and not surprising that modern American culture sees an array of books, TED Talks, and thought leaders emerge, praising the notions of “authenticity” and “vulnerability”, because the simulation isn’t complete until it convinces you that it isn’t a simulation.

Dante comments on the action of committing sin while simultaneously attempting to repent it and provides insight into our contradictory culture of authenticity. In canto seventeen (canto being Italian for song), Dante and Virgil travel to the eighth circle of Hell, the circle of fraud, and examine the sinners within the pit. Here, sinners burn in their own private fire with the flame engulfing and obscuring their whole form. Guido da Montefeltro, who sinned by fraudulently counseling Pope Boniface VIII, discusses his attempt to preemptively absolve sins he planned to commit. However, a demon within this circle points out the contradiction inherent in attempting to absolve oneself of a sin they still intend to commit. Dante’s commentary applies to the modern day narcissist in the same way - calculated attempts at authenticity, which can be likened to a rejection of the sin of fraud, is still an intended commitment of fraud and thereby leads one to Hell. And fitting the theme within Inferno that the punishment matches the sin, the narcissist privately suffers in their internal void just as the sinners of the eighth circle burn privately in their own fires.

The valuation of image over authenticity, when practiced on a societal level, leads to a very specific dynamic within the workforce that Lasch expands upon:

The growth of bureaucracy creates an intricate network of personal relations, puts a premium on social skills, and makes the unbridled egotism of the American Adam untenable.

What is required to succeed in late capitalism’s corporate world is a fluency in business ontology. The American capitalist’s toolkit is hollow politeness and faculty in word choice. It’s not an accident that business speak and corporate jargon have been subject to mockery by comedians. The deception rampant within the corporate world mirrors the deception of public declarations of wealth in the US. Politicians within this country brag of the virtue of their economic policies by citing the gradual improvement of legible metrics of economic health such as the DOW index while ignoring the Reality that much of the wealth generated returns to the managerial class. And while all of this happens, the beloved narrative of America as a center for economic mobility decays. Dante’s commentary throughout Inferno includes discussions of the corruption of various Italian societies, specifically in the notion that patterns of sin committed on the individual level lead to communal sin. While the pathologies of modern American society and medieval Italy are different, the underlying emergent properties of decaying societies remain and Dante’s thoughts on communal sin persist.

III.

Nothing captures what lay underneath the narcissist’s veneer better than the internal monologue of Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. In the book, a hallmark of transgressive fiction and representations of 90’s America, Bateman admits:

My pain is constant and sharp and I do not hope for a better world for anyone, in fact I want my pain to be inflicted on others. I want no one to escape, but even after admitting this there is no catharsis, my punishment continues to elude me and I gain no deeper knowledge of myself

From the void that the simulacrum emerges from, all that exists is an undercurrent of rage and wrath - a desire to consume the external world and diffuse nothingness. Lasch deconstructs Bateman and characterizes his internal burning as emblematic of our culture:

...a belief that excellence usually is achieved at the expense of others, that competition tends to become murderous unless balanced by cooperation, and that athletic rivalry, if it gets out of hand, gives expression to the inner rage contemporary man desperately seeks to stifle.

And while the above quote makes specific mention of competition, one must not forget that in the culture of narcissism, the theatrics of existence entail a necessary reality of competition among facade bearers. Simply put, the only escape from the rage is to reject the game unfolding and reclaim authenticity. But what would Dante say of this rage? Canto VIII of Inferno answers the question, portraying a swamp full of the wrathful constantly fighting among each other. There is no rhyme or reason to the violence. As always in Dantean fashion, the punishment matches the crime and the sinners of the circle of wrath suffer from undeserved violence. As Dante passes through this circle, he encounters Filipo Argenti, a Black Guelph from Florence who is a historical figure Dante purposefully chose to include in this circle. In real life Florence, Argenti had shown violence to Dante before and opposed Dante’s return from exile - two clear acts of wrath. Observing the violence that occurs within this circle of Hell, readers pick up on Dante’s underlying message - that wrath acted upon results in wrath returned. And so, as Dante leaves this circle, Argenti is torn apart by several other sinners within this circle.

As always, the pathologies of the individual are reflected on a cultural level. Nothing encapsulates the muted rage of the narcissist more than modern politics. Many have noted that politics, in particular the language within politics, have become more polarized and divisive over the past few decades. A renewed interest in identity politics serves as a vessel for either of the two sides to vent their rage. The right wing of America permits undercurrents of nationalism and xenophobia, with frequent nods to ideologies that endorse violence against minority groups. On the other side, the left wing promotes an identity politics of their own. The resentment towards a perceived privileged class of American society hides itself under the guise of equality and social justice. Mass media capitalizes on the highly polarized illusion of choice and the underlying pathology of the American public to perpetuate a politics of rage. Our rage and wrath has been so cleanly directed towards an appropriate target, our means of voicing anger organized and so simply presented, that it becomes impossible to resist the seduction of party theatrics. The corruption, however, lies in the reality that stances are no longer taken out of principles that are thought out, but for nothing more than hatred for the other side. Victory is sought not for the success of one’s own ideals, but to see the other side suffer. We have all become the denizens of the fifth circle, succumbing to wrath in our collective casting off of shared humanity. The senseless violence that the sinners of wrath inflict on each other mirrors the venom with which we speak of the other.

In the media and our politicians channeling our rage, we have turned politics into a performance. It becomes necessary to define oneself according to the entire party line. There is no room for nuance or disagreement. In America, one cannot say that they agree with some aspects of the democratic party platform and some aspects of the Republican platform or say that they refuse to vote for either candidate, otherwise the image disintegrates. Lasch’s comment about American sports rings true for the political arena:

The mania for winning has encouraged an exaggerated emphasis on the competitive side of sport, to the exclusion of the more modest but more satisfying experiences of cooperation and competence.

The picture painted looks bleak in the end. Several theorists of our time have captured other perspectives on the grim outlook for modern American politics. In his book Amusing Ourselves To Death, Neil Postman analyzes the media and its role to play in the current climate, which he likens to Huxley’s dystopia. In the massively influential work Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher argues that we are at a point where it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism in its current form. He goes on to describe capitalism as a cultural phenomenon on top of an economic system and draws a similar portrait to Lasch’s culture of narcissism. With all of this said, it is easy to give up hope on modern culture and retreat into a sea of nihilism. However, Dante’s Inferno provides us with more than just a diagnosis to the modern problem, he also provides a solution.

IV.

To find a solution to the crisis of the modern day, we follow Dante’s desire to view the Divine Comedy as an allegorical work. In particular, we ask: what is the significance of Virgil leading Dante through the underworld and why it seems that the circles of Hell are ordered in such a way that the cognitive faculties of the prisoners decrease the farther in we go. And most importantly, we must remember that Dante the protagonist represents us, the average person, as his journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven symbolize the universal human experience.

Virgil represents reason throughout Inferno. Dante Alighieri reveals his admiration for Virgil as soon as the first canto. Throughout Inferno, Virgil serves as a parental figure for Dante, often comforting the traveler during his terrifying descent into Hell. Virgil also understands the inner workings of Hell and what the residents of Hell did during their life to earn their place. In this way, Dante communicates that reason is a tool to understand the inner workings of Hell and suffering from the start of the epic. As Virgil leads Dante further into Hell, he reminds Dante of the divine nature of Dante’s journey, culminating in the two meeting Lucifer at the absolute bottom of the ninth circle. In the final canto of the poem, Virgil takes Dante and climbs down Lucifer’s hide to the bottom of Hell and then leads Dante back to safety through a secret passageway so that the pilgrim may begin his ascent of Mount Purgatory. Virgil’s presence and actions communicate that reason allows one to transcend destructive action and begin the path towards peace.

In contrast to the clear cognition of Virgil, the residents of Hell lack cognition, with this lack increasing as Virgil and the pilgrim go farther into Hell. In the first circle, Limbo, we find “noble pagans” who couldn’t have subscribed to the Christian theology because they lived before its existence. Taken in context, this would mean that Dante is saving historical figures who he viewed as moral but not Christian. In our analysis, their religiosity is unimportant, and we focus on the fact that they maintain their cognitive faculties. During their descent into Hell, Virgil and Dante comment on the logic the sinners of Hell use in their justifying their actions. As we progress deeper, we note a growing dissonance between the language the sinners use to describe themselves and reality as portrayed by Dante and Virgil. This progression culminates in the encounter with Lucifer who lacks all cognitive faculties in his frozen jail cell at the bottom of Hell. He can do nothing but suffer, shiver, and move his wings, blowing gusts of wind through Hell. In the whole development, sinners reveal their cognitive faculties in their display of self-awareness, with the most sinful completely lacking cognition and any grasp of reality. As readers, we can understand that one creates and maintains their suffering by losing awareness and cognitive faculties.

And how does all of this create a solution to the culture of narcissism? It is clear that we must reclaim awareness and begin using reason to reverse the damaging effects of the culture we participate in. The solution cannot be employed by the state, as no system will act in a manner in which it dismantles itself. More importantly, nothing can help an individual cultivate awareness and reason except for the individual themself. It becomes clear that a solution will be bottom up and individual based.

The first step towards relieving individual suffering in the culture of narcissism is to create awareness of one’s actions and where the motivation for these actions comes from. Are we acting in a way that is authentic to our core or are we continuing to play a character that we have been taught to play? Is our anger well thought out or is it a conveniently channeled rage at a caricature of reality that the media and institutions create? Cultivating this awareness is not simple. Awareness is not a light switch that can be turned on but something that must be practiced and strengthened.

The second step is to think independently. Where are our principles coming from? Have we sufficiently questioned why we believe what we believe and determined that our beliefs come not from wounded ego and emotional needs but from carefully thought out principles? Nowadays, there is a fusion of entertainment and information as can be seen in the theatrics of politics and ideology. Can we separate these theatrics from the messages and reason independently? This is also not an easy matter. It relies on a solid awareness that allows one to connect with reality and then demands discipline and honesty in coming to conclusions.

In this process, we can alleviate ourselves from the suffering and nihilism our culture inflicts upon us and reclaim both our authenticity and sovereignty. Lasch writes in The Culture of Narcissism:

Every society reproduces its culture—its norms, its underlying assumptions, its modes of organizing experience—in the individual, in the form of personality. As Durkheim said, personality is the individual socialized.

I’d like to wager that the opposite is true as well. That with a shift in the psyche of enough individuals within a society, the culture itself changes to reflect emergent properties of network effects of that psyche. Certainly a shift to a healthier psyche for an individual has positive effects - thus the prospects for a healthier culture seem promising. And hopefully, we may complete what initially drove Dante and Lasch to write their respective works.